Understanding Corrective Exercise

Receiving regular massage therapy is widely recognized for its effectiveness in keeping most chronic pain conditions at bay. Despite this, pain symptoms usually return, when clients increase their physical activity or miss scheduled sessions. This observation became evident to me a few years into my career, leading to a realization: massage therapy alone cannot resolve every chronic condition.

Motivated by a desire to help clients achieve lasting, self-sustained well-being, I began examining the biomechanics of common chronic issues. Through this deeper exploration, I discovered a recurring foundational theme —muscle weakness.

Importantly, the weakness was not always general, but localized in specific muscles, with a particular emphasis on those responsible for stability.

This insight inspired me to pursue certification as a personal trainer and, subsequently, as a functional trainer. My goal was to offer a multi-dimensional approach to addressing my clients’ chronic imbalances, combining massage therapy with corrective exercise to target underlying limitations.

Biotensegrity

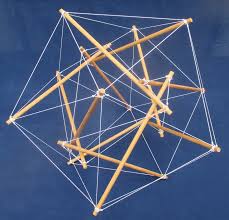

While training to become a massage therapist, I was introduced to the concept of biotensegrity—a physiological principle that is not widely known outside the community of bodyworkers. This foundational construct shaped my perspective on the body’s structure and function.

Understanding biotensegrity provided a framework for how I viewed the human body. Rather than seeing the body as a collection of isolated parts, I began to appreciate the interconnectedness of tissues and the importance of structural balance. This realization became a guiding force in how I approached both assessment and intervention, further informing the integration of corrective exercise into my practice.

The Tent Analogy: Understanding Biotensegrity

To illustrate the principle of biotensegrity, consider the structure of a tent. In this analogy, the poles can be seen as representing our bones, while the ropes act as our muscles. Just as a tent relies on the proper tension of its ropes to maintain its shape and functionality, our bodies depend on the appropriate tension within muscles to support and stabilize the skeletal system. If the ropes of a tent are too loose or too tight, the structure becomes unstable and may collapse. In the same way, balanced tension within our muscles is essential for maintaining structural integrity and optimal movement in the human body.

Basically, our body’s structure is maintained by the coordinated support of bones and connective tissues. Muscles, tendons, ligaments, and fascia work together to stabilize our skeleton and enable ideal movement. Through a coordinated application of pressure, these tissues support posture and facilitate optimal functionality.

How We Lose Structural Integrity

Balance is a fundamental component of our physical health, just as it is in other aspects of life. In the realm of bodily function, both our actions and our inactions can disrupt this crucial balance, potentially leading to structural imbalances over time.

Our bodies are remarkably adept at adapting to the demands placed upon them. With repeated exposure to specific physical tasks, the body becomes increasingly efficient at performing those actions. This adaptability, however, comes with a downside: repetitive movements are the leading cause of skeletal-muscular imbalances.

When we engage in a particular activity (or sustained position) frequently, we rely on a specific group of muscles to complete the task. Over time, this repeated use can result in dysfunction within the muscle tissues. These dysfunctions may manifest as increased tension, reduced muscle tone (flaccidity), the development of adhesions, or even more serious issues such as strains and tears.

Here’s a short video illustrating muscle tissue dysfunction within a very common pelvic instability Rotated hip dysfunction

Ultimately, the repetitive nature of certain physical activities disrupts the body’s structural integrity, making it essential to be mindful of how our habits impact muscular balance and overall function.

Coupling counter actions such as reverse movements and antagonist muscle strengthening, as well as restorative activities like stretching and massage can help prevent dysfunction within the tissues.

The Impact of Inaction and Sedentary Lifestyles on Muscle Balance

Muscle tension imbalances are not only the result of repetitive movements; inactions and sedentary lifestyles can also contribute to the issue.

Because our bodies are highly efficient at conserving energy, the principle of “what you don’t use, you lose” becomes especially relevant. When certain structural muscles are underused due to lack of movement or prolonged inactivity, they gradually weaken. This loss of strength can lead to instability within the body’s support system, making it more vulnerable to dysfunction and imbalance.

The Role of Corrective Exercises

When structural imbalances persist without intervention, the body will eventually respond with signals such as discomfort and, over time, pain. These symptoms serve as feedback, alerting us to the need for a change in our habits and/or lifestyle. If chronic pain is ignored and left untreated, it can progress, leading to greater imbalance and imposing severe limitations on physical function.

In many cases, when individuals experience discomfort or pain related to muscle imbalances, the initial approach involves the use of medication. These medications are primarily intended to manage symptoms; however, they often come with undesirable side effects. Importantly, while medication may provide temporary relief by masking the pain, it does not address the underlying cause of the problem. If medications fail to provide adequate relief, more invasive interventions, such as surgical procedures to repair, or replace the affected body part are usually considered.

However, it is important to recognize that before reaching the point where surgical intervention becomes necessary, there are often opportunities to restore balance through retraining the body. This is where corrective exercises are essential. By addressing the underlying structural issues, these exercises provide a means to correct imbalances and potentially prevent the need for more drastic measures.

Case Study: Addressing Pelvic and Hip Muscle Imbalances

Common Imbalances and Resulting Conditions

One of the most frequent imbalances observed in clients involves the pelvic and hip region. This imbalance can manifest as sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction, herniation of lower lumbar disc, and knee joint dysfunction. All these conditions can be traced directly to instability in the pelvic and hip area.

The Role of Hip Stabilizers

The hip joint relies on a complex network of 17 to 20 different muscles for proper function, which can make pinpointing the precise source of weakness challenging. Among these, the gluteus muscle group serves as the primary stabilizer for the pelvis and hip. Each muscle within this group contributes to hip support in a specific way, depending on the direction of movement. This understanding enables practitioners to use targeted strength and mobility assessments to identify the location of muscular weakness.

Identifying the Source of Weakness

Experience shows that when clients present with one or more of the aforementioned conditions, they almost always demonstrate weakness in external hip rotation on one or both sides. The main responsibility for external hip rotation falls to the gluteus medius and minimus, as well as their underlying muscles. These muscles are the first to activate and stabilize the hip joint during any movements that stem from pushing off the foot (such as walking or rising from a squat position). If these muscles are too weak to fulfill this role, other nearby muscles are forced to compensate.

Compensatory Patterns and the Tensor Fasciae Latae

When the gluteus medius is unable to perform its stabilizing function, the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) muscle is the first to step in. Located adjacent to the gluteus medius but positioned on the anterior (front) side of the pelvic bone, the tensor fasciae latae primarily attaches the iliotibial (IT) band to the pelvis and facilitates abduction (lateral movement) of the leg. The IT band, in turn, helps stabilize the knee and upper leg muscles. Understanding this relationship clarifies how dysfunctional movement patterns can develop if the tensor fasciae latae is forced to compensate for a weak gluteus medius, performing tasks it is not primarily designed for.

Initial Symptoms of Hip Muscle Imbalance

When the gluteus medius muscle is underactive and the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) becomes overactive, a distinct set of symptoms may arise. The earliest indication is typically lateral hip pain, which results from inflammation within the overstressed muscle fibers. This pain may not remain localized; instead, it can radiate upward to the buttocks and lower back or downward along the side of the leg, reaching the knee area. In some cases, discomfort is only perceived at the sacroiliac (SI) joint or directly at the knee.

Biomechanical Effects and Associated Pain

Regardless of where the pain manifests, the underlying biomechanics are consistent when stepping onto a leg dominated by an overactive TFL. This situation places a significant amount of torque on both the knee and hip joints. At the knee, this torque leads to instability and contributes to the gradual wear and tear of ligaments and cartilage. At the hip, the persistent lateral pull exerted on the pelvis can result in dislocation of the SI joint, and, over time, may progress to low back disk protrusions.

Corrective Exercises: Principles and Process

Corrective exercises are grounded in the three essential elements of functional fitness:

Key Elements of Functional Fitness

- Flexibility

- Mobility

- Strength

All three elements are considered integral to a comprehensive corrective exercise program. While strength is often prioritized, particularly for joint stability, focusing solely on strength without considering flexibility and mobility may limit the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving joint stability and movement quality.

Steps to Correcting Improper Movement Patterns

- Activation: The first step involves enhancing the neuro-muscular connection to the target muscle. This is achieved through exercises that specifically isolate the weak muscle, ensuring it is efficiently engaged and “switched on.”

- Strengthening: Once activation is established, the next step is to increase the strength and capacity of the target muscle fibers. This phase also relies on isolated exercises to progressively build muscle strength.

- Integration: In the final step, the goal is to retrain the muscle group to work together with other muscles proficiently. This is done through compound movements with specific activation cues that promote improved muscle synergy and coordinated function.

Progress through these steps is determined by consistent testing and assessment of the client. The duration and emphasis on each phase are tailored based on ongoing observation and evaluation, ensuring that corrective strategies are responsive to individual needs and progress.

Corrective vs Conventional Training Sessions

Conventional Training Sessions

Most personal training clients are accustomed to traditional workout routines designed to build general strength and fitness. During these sessions, trainers guide clients through loaded compound movements that engage multiple muscle groups, emphasizing proper form and encouraging increased intensity to promote progression. Clients typically focus on pushing themselves through the exercises, responding to the trainer’s audible instructions and cues.

While conventional training can be highly effective—especially when guided by a skilled trainer—it may not address underlying structural imbalances. In the majority of clients, these imbalances are present. Without targeted intervention, dysfunctional compensation patterns can be reinforced, potentially resulting in immediate symptoms or gradual wear and tear that may only become apparent over time.

Corrective Exercise Sessions

Corrective exercise primarily consists of short, controlled movements that target specific muscles and/or movement patterns. The success of these exercises relies heavily on the trainer’s ability to communicate precise movement cues and the client’s capacity to maintain concentrated attention on the targeted muscles.

The client’s mental approach during corrective exercise plays a significant role in achieving successful outcomes. Unlike conventional training, where clients often rely on external cues and motivation from the trainer, corrective exercise demands a higher degree of internal focus and mind-body connection. Cues for adjustments often come quietly from within. This approach corrects movement patterns and increases body awareness, leading to better overall well-being.

Integrating Corrective and Conventional Training

Both corrective and conventional training styles serve important functions within personal training. Each approach addresses different aspects of a client’s fitness and well-being, and when used together, they can create a more comprehensive and effective program. By skillfully blending these methods, trainers can help clients achieve better results, improving both functional movement and overall strength.

Personalization Based on Client Goals and Needs

The optimal approach depends on the client’s individual goals and current physical condition. Understanding what the client hopes to achieve, as well as their unique structural or functional needs, is essential. This personalized strategy ensures that the training plan is tailored specifically to the client, maximizing the benefits of both corrective and conventional exercises.

For more information on available services for customized fitness programs, please check out these links:

FUNCTIONAL FITNESS

FOUNDATION FITNESS PROGRAM